Transcription

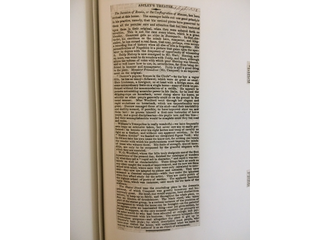

ASTLEY’S THEATRE.

Invasion of Russia, or the Conflagration of Moscow, has been revived at this house. The manager holds out one good principle in his practice, namely, that his revived pieces have preserved in them all the peculiar care and attention that had been bestowed upon them in their original, when they were ushered forth as novelties. This is not the case every where, which is a great blunder. Gomersal gets no older in Bounaparte. In that character, his exertions as the mimic hero, conqueror, and king-maker, he has earned a real fame, that may, perhaps, even occupy a recording line of history when all else of him is forgotten. His personification of Napoleon is a picture that gains upon the spectator in degree with the frequency of opportunity of witnessing it. Teddy Malony is now consigned to Mr. Hart. Herring now, no more, was wont to do wonders with Teddy, and Hart, although minus the volume of voice with which poor Herring was blessed, and so well knew how to use, is, nevertheless, far from being deficient in humour and management. Teddy is still a great thing in the piece. Monsieur Frieandeau (Mr. Conquest) is an improvement on the original.

“Ducrow’s popular Scenes in the Circle”—by the bye a vague title, he has so many—followed, which were as great as usual. Herr Lindeman, a foreigner, or at least with a foreign name, did some extraordinary feats on a single horse—many of which he performed without the accommodation of a saddle. He appears to possess astonishing muscular power in his limbs, for he used the skipping-rope on horseback, never rising above his knees, as adroitly as other people generally could do on the ground in the usual manner. Miss Woolford went through her elegant and rapid evolutions on horseback, which are unquestionably very great. Ducrow managed three of his stud—and their tractability and docility seemed, if possible, to have improved since we saw them last: he proves himself a first-rate instructor of horse youth, and a good disciplinarian—his pupils love and fear him—and their accomplishments would be complete could they but read and write.

Williams’s Trampoline is really wonderful—we have frequently seen leaps as extensive taken, but never saw any so easily performed: he bounds over his horses and troop of cavalry as light as a feather, and without any apparent exertion. In the “Modern Alcides” we fancied we recognized Signor Valdi: why he did not take his own name we know not, for nothing can lessen the wonder with which his performances must impress the minds of these who witnessed them. His feats of strength, almost incredible, are only to be surpassed by the graceful elegance with which they are executed.

W. G. Woolford, whom the bills truly designate one of the first equestrians of the present day, finished the catalogue of wonders by what they call a “rapid act in character,” and rapid it was certainly as well as characteristic. These things have as much as any other caught the march of improvement, and we now see them mixed with mind, where once they were only calculated to astonish—they now are adapted to please and astonish. They have assumed a classical complexion—while they make the ignorant stare they afford study for the artist. They are really poetry of the highest school of poetry of motion. The applause bestowed upon them, which was immense, said much for the taste of the audience.

The Statue Steed was the concluding piece in the dramatic personae, of which Conquest was greatly humorous and humorously great. He must, one would suppose, have studied from nature, to keep up so fairly, and throughout the whole piece, so fine an illusion of drunkenness. The black steed, who takes part of the statue group, is a curious instance of the precision of the management to which the horse can be brought—on the pedestal he appears quite an inanimated thing—and yet gives motion, by signal we suppose, at the very moment required—as promptly as an actor would do who had been educated at college, and perfectly conversant with his business. The scenery is superb—the processions gorgeous—and altogether the piece is got up in Ducrow’s best style; by which description most people, who have ever visited the house, will understand what we mean to convey in our brief notice of it as an object of amusement.