Transcription

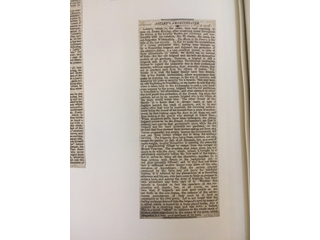

ASTLEY’S AMPHITHEATRE.

Astley’s, which in the olden time used regularly to open on Easter Monday, after remaining closed throughout the winter, is the holyday theatre par excellence, and, consistently with his vocation, Mr. W. Cooke, the lessee, has not forgotten Whitsuntide. The Horse of the Cavern is the title of the last novelty. In this we make the acquaintance of a young gentleman who having been brought up by a Neapolitan brigand and followed the profession of his adoptive father, is a very excellent person, in spite of these antecedents—or rather, we should say, on account of them—for the old brigand and his wife are themselves models of all goodness. However, a brigand is still a brigand, and, as the Neapolitan Government obstinately chooses to regard the admirable trio in their professional capacity, without considering their domestic virtues, they are in constant peril from the officers of justice. Fortunate it is that they happy family have two friends. One is the French Ambassador, whose acquaintance they make by stopping his carriage in the way of business, and detaining his niece as security for a ransom. This may seem an odd beginning to friendship, so we hasten to add that he niece is taken back to the Ambassador in such a very handsome manner by the young brigand that the old gentleman is boundless in his admiration, and even attempts to afford the bold youth the protection of the French flag when the soldiers, led on by an apostate brigand who is the villain of the story, would arrest him. The other friend of the family is a horse that is always ready to take a fugitive beyond the reach of pursuers, and to do any useful office that may be required, his crowning achievement being the rescue of his masters from a place of confinement, by first kicking open the door to let them out, and then kicking at the guards who attempt to follow them. When numerous perils have been undergone, the young brigand proves to be the French Ambassador’s son (lost in infancy) and marries that gentleman’s niece, while the old brigand and the band generally are pardoned, on the ground that they pursued their lawless calling not from any vicious propensity, but simply because the Government did not pay them certain arrears due to them for military services. The brigands, thus being State creditors, not only accept the pardon in full of all demands, but, as a sort of make-weight, employ themselves in assisting the peasantry of a neighbouring village to escape from the ravages of Mount Vesuvius. The eruption that takes place has not much to do with the story, which, indeed, is brought to a satisfactory conclusion before the first spirt of fire begins, but it serves to being all the characters together in a final tableau, with flames in the background and a red glow generally diffused; and he who does not think this a sufficient motive knows very little of the construction of hippodrome. That the serious interest awakened by the fable may not prove too painfully intense, it is relieve by the pleasantries of a travelling alderman and his won, who have come to Italy on purpose to write a book, and assume the dress of brigands, that their own adventures may form part of it. Whether this episode is founded on fact the members of the corporation will decide; but, at all events, we must own that, if brigands are such good people as are set forth in the new drama, the costume of the adventurous mountaineer of Italy must be at least as respectable as the civic gown. Let us not forget that the daring cockneys descend into the brigand’s cave by means of a wheel which is turned by a horse placed inside, like a squirrel in a revolving cage, and lets down a basked. This is a novel “effect” in addition to the whole stock of wonted effects introduced in the course of the piece, which altogether is a very good specimen of its kind.